The Artist

Sue Gill Rose

Sue Gill Rose was born at Randolph Air Force Base in Universal City, Texas, near San Antonio. Sue was the oldest of 4 children, 2 brothers 1 sister. Her father, Edward Washington Rose II was a rear bombardier in the Air Force, Randolph Field, during WWII. Her father moved the family back to Dallas after the war. Her mother, Cora Sue Gill, grew up in Muskogee, Oklahoma and moved to Dallas to live with her sister as a young woman.

Sue’s mother encouraged an interest in art by constantly taking Sue to various art exhibits and enrolling her in art classes. From age 10 to 12 Sue studied painting at the Dallas Museum of Art at the State Fair taking the city bus to her classes. Her budding art awareness was cultivated from lessons by Ruth Duncan Harrison (1909 – 1996), well known artist in the Dallas area. I met the artist, Chapman Kelly (b. 1932), when I was a lifeguard at University Park swimming pool, at age 15. I met him because I taught his children swimming lessons and we would chat about art at the pool. Kelly was the new trendy Dallas artist and was encouraging to me… he saw my work, he befriended me. I liked his work, his color, and it was the first time I was introduced to anything abstract. I liked the looseness, the color and the spontaneity in his paintings. I don’t remember being introduced to abstract before. It was also my first experience being exposed to somebody who did not fit or conform to my parents’ social strata he seemed very avant-garde; he was kind of a hippie. Everyone asked me, ‘Did you know that was Chapman Kelly?’

Her first year out of High School (1956), Sue attended the University of Colorado, but returned to Dallas after her freshman year. When Sue moved back to Dallas she began seriously studying art under Jerry Bywaters (1906-1989) at Southern Methodist University. Bywaters, a proponent of the standard of freedom of expression, served from 1943 to 1964 as director of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts while mounting ambitious exhibitions such as Religious Art of the Western World (1958) and simultaneously teaching art and art history at SMU.

Her first year out of High School (1956), Sue attended the University of Colorado, but returned to Dallas after her freshman year. When Sue moved back to Dallas she began seriously studying art under Jerry Bywaters (1906-1989) at Southern Methodist University. Bywaters, a proponent of the standard of freedom of expression, served from 1943 to 1964 as director of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts while mounting ambitious exhibitions such as Religious Art of the Western World (1958) and simultaneously teaching art and art history at SMU.

After graduating from SMU in 1960 Sue moved to New York City. At first she worked for McCall’s Magazine writing and promoting the Betsy McCall column. She then worked for Thorpe Brothers doing restoration of antique furniture and specialized in gold leaf. “I was 24 years old. I went to all the Broadway shows, had the great New York experience.

“I really thought I wanted to be married more than anything when I met David Farmer, a graduate of Rice University.” Sue and David married and immediately moved to Shreveport, Louisiana. Sue totally switched gears into a completely different lifestyle, and had four children within five years.

“I really thought I wanted to be married more than anything when I met David Farmer, a graduate of Rice University.” Sue and David married and immediately moved to Shreveport, Louisiana. Sue totally switched gears into a completely different lifestyle, and had four children within five years.

Art was secondary in her life until after the children were almost grown. During their formative years Sue’s artistic outlet was primarily craft works like crocheting, knitting, tatting, and cross stitch. The ease that you can pick up and put down that sort of work and the fact that she could still be creating appealed to her. As a child Sue particularly liked puzzles because she liked the idea of putting something together and in craft work she was always putting something together. “I am such a type “A” personality that I can get honed in on something and everything else goes out the window. I like a challenge, and art is like putting a puzzle together to me – I like that.”

After a divorce, her mother, Cora, went back to school and received her Masters degree from the University of Dallas. This had a tremendous influence on Sue. Her love of literature and learning was definitely instilled in her from her mother. “In 1987 I decided to go back to school to get my own Masters’ Degree. That’s when I really threw myself into my art.

After a divorce, her mother, Cora, went back to school and received her Masters degree from the University of Dallas. This had a tremendous influence on Sue. Her love of literature and learning was definitely instilled in her from her mother. “In 1987 I decided to go back to school to get my own Masters’ Degree. That’s when I really threw myself into my art.

“Going back to school was my salvation. I love learning new things. I would be happy being the perpetual student. I was able to learn and do and create with that part of me that had been stifled.” While working on her Masters in Liberal Arts at Louisiana State University, Sue studied Greek Classics, Great Literature, Woodworking, Sculpture, Drawing; she went to lectures, she did installations, and painted. And painted. James Lake, her professor, taught what became one of her most influential courses, Southern Literature. Sue enjoyed reading the great 20th century Southern authors and relating to the settings, the characters, and the experiences. Eventually these subconscious influences would play a significant role in her artwork. Read more about the Southern Reflection Series

“Going back to school was my salvation. I love learning new things. I would be happy being the perpetual student. I was able to learn and do and create with that part of me that had been stifled.” While working on her Masters in Liberal Arts at Louisiana State University, Sue studied Greek Classics, Great Literature, Woodworking, Sculpture, Drawing; she went to lectures, she did installations, and painted. And painted. James Lake, her professor, taught what became one of her most influential courses, Southern Literature. Sue enjoyed reading the great 20th century Southern authors and relating to the settings, the characters, and the experiences. Eventually these subconscious influences would play a significant role in her artwork. Read more about the Southern Reflection Series

Mary Flannery O’Connor (1925 -1964) who often wrote in a Southern Gothic style and relied heavily on regional settings and — it was said — grotesque characters. But she has remarked, “Anything that comes out of the South is going to be called grotesque by the northern critic, unless it is grotesque, in which case it is going to be called realistic.”

P.J. O’Rourke[Patrick Jake] (b. 1947 Toledo, Ohio) O’Rourke has been described as a conservative American political satirist, journalist, and writer. He wrote articles for numerous publications before joining National Lampoon in 1973, where he served as managing editor among other roles and authored countless articles as well. He became foreign-affairs desk chief at Rolling Stone, where he remained until 2001.

William Faulkner (1897-1962) Credited as one who helped establish the American Novel as acceptable literature. Most works have a setting in his native state of Mississippi and are always influenced by the history and culture of the South. He is considered one of the most important “Southern Writers”, and was awarded the Nobel Prize at the early age of 52.

Pat Conroy (b.1945 Atlanta, Georgia) His stories are heavily influenced by his childhood in the deep. Conroy claims to have moved 23 times before he was 18. He accepted a job teaching children in a one-room schoolhouse on remote Daufuskie Island, South Carolina. Conroy was fired at the conclusion of his first year and he wrote “The Water Is Wide” based on his experiences there. The book won Conroy a humanitarian award from the National Education Association and was made into a feature film, Conrack, starring Jon Voight in 1974. In 1976, Conroy published his first novel, The Great Santini. The novel was made into a film in 1979, starring Robert Duvall.

“School had opened so many doors for me. All of a sudden things began to expand and I learned to laugh at myself and not take myself so seriously. I began to paint weekly at the Barnwell Art and Garden Center with a group of active Shreveport artists. It was during this time I joined the Hoover Watercolor Society and At-the-Loft Studios. Tama Nathan became my mentor and teacher even though I had known her for a long time. One day Tama and I drove to the SMU Meadows Museum to see the Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008) exhibit, and we had lunch with him. His work was a kind of painting combination with sculpture…some installations but mostly work on canvas. Tama introduced me to Clyde Connell (1901-1998) just before she did the Bound People sculptures.Clyde previously had studio space in At-the-Loft and she became a big influence and inspiration to us all.”

At-the-Loft was a downtown building that housed studio space for artists to paint during the late 80’s to mid 90’s. But there was more to the space than just rent. Artists could go there and exchange ideas. It was a place of camaraderie. Janet Parker, Nevelyn Brown, Tama Nathan, Berk Bourne, and Lucille Reed all had studios there at one time or another. These were the progressive artists of the day in the Shreveport area. The At-the-Loft artists were the same people who brought feminist artist Judy Chicago (b. 1939) and independent alternative media artist/writer/poet Alan Sondheim(b.1943) to Shreveport to speak. They invited outside artists to set up installations and exhibitions in the space and participated with other groups such as the Artist’s Transit, the Princess Park Works-In-Progress group, SRAC’s (Shreveport Regional Artists Council) public sculpture projects, and the Red River Revel. The artists that migrated to this group were acutely sensitive to the larger cultural currents related to slavery, poverty, education, religion, and judicial injustice that often were reflected in their work. There were potters, jewelers, and sculptors, fabric, and mixed media artists as well.

At-the-Loft was a downtown building that housed studio space for artists to paint during the late 80’s to mid 90’s. But there was more to the space than just rent. Artists could go there and exchange ideas. It was a place of camaraderie. Janet Parker, Nevelyn Brown, Tama Nathan, Berk Bourne, and Lucille Reed all had studios there at one time or another. These were the progressive artists of the day in the Shreveport area. The At-the-Loft artists were the same people who brought feminist artist Judy Chicago (b. 1939) and independent alternative media artist/writer/poet Alan Sondheim(b.1943) to Shreveport to speak. They invited outside artists to set up installations and exhibitions in the space and participated with other groups such as the Artist’s Transit, the Princess Park Works-In-Progress group, SRAC’s (Shreveport Regional Artists Council) public sculpture projects, and the Red River Revel. The artists that migrated to this group were acutely sensitive to the larger cultural currents related to slavery, poverty, education, religion, and judicial injustice that often were reflected in their work. There were potters, jewelers, and sculptors, fabric, and mixed media artists as well.

The time Sue spent with this viable art community was the impetus for much of her thesis on Regionalism. Part of this thesis was a slide registry of visual artists in 12 parishes in North Louisiana which is still in the archives of LSU-S and also has been used by the Shreveport Regional Arts Council. “My thesis featured the regional artists Lucille Reed, Elsie Faith, and her daughter Nevelyn Brown. It was very interesting because of the three artists – the one that remained in Louisiana, stayed more traditional, and stuck in her southern roots. It was simple to see that as the artists traveled and expanded their world, their art changed. The artists that had been all over the world became more abstract, more avant-garde. The one that remained locked in this little region stayed very traditional. When I was doing my thesis I became very interested in naive and primitive artists like M.C. 5 CENT Jones (1918 -2003) and the Reverend Howard Finster (1916-2001).” Sue started teaching art classes at Barnwell Art and Garden Center while getting her Masters. She also worked for about six years with Artport to place work by local artists in the Shreveport Regional Airport. In the inaugural 1990 Artport exhibition Sue won the VIP Travel Agency Award, for her watercolor, “Mardi Gras”.

Louisiana Tech at Ruston had a much better Art Department than LSU -Shreveport. I drove twice a week about an hour and ½ away to take the more specialized art courses such as Color Theory. Six months of Color Theory, cutting little squares out, is tedious work.” Sue also studied watercolor with M. Douglas Walton during summer workshops. These intense workshops were fun for Sue painting for 8 hours during the day after staying up all night because it was too hot to sleep in the dormitory. Besides watercolor, Douglas Walton also taught her the importance of a limited palette. “I learned FC2 (Found Order from Chaos). I use it more with watercolors. I still use this today when teaching my students. By taking 3 colors, a maximum of 5 colors and randomly with a big brush cover the background, the whole sheet of paper. Then place the drawing over that using a light box and paint over that. So that all this mixture, which are colors in the palette anyway, these colors that ordinarily would not be there, show through and give much more life to the painting. It is a very, very successful technique and it has made me realize my love of patterning in painting. I like the idea of putting pieces together. I also learned the importance of useful design elements from Douglas Walton. Usually my preliminary drawings are first done on a piece of poster board. This acts as my sketch pad. I think rhythm, movement, color, and composition are more important. I guess right now I want to paint something fun and not just a pretty picture. I want my work to be recognized and if I did landscapes and seascapes I would be one of 72,000 doing the same thing and I don’t want to do that.”

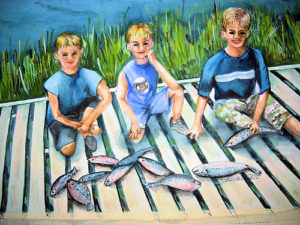

“Now that I am settled my life I don’t feel the need to have all this introspective, emotion coming out in my paintings.” When her life was still in chaos she often would not see this struggle reflected in her painting until after she finished the work. “Odd Man Out”, a painting with the school of fish going in one direction and a lone fish going the opposite way, is a good example. Some of the installations and some of the in-your-face-stuff I did in Shreveport in the early 90’s was coming out stuff; making a statement. I don’t find that particularly necessary now. Although I do think in my own way, in what I am doing currently, I am making a type of statement in saying that there is joy, humor, and there is fun in the most ordinary part of everyday life.”

“Tama Nathan gave me a lithograph when I finished my Masters in 1990 titled, To Sue, Who Now Has Roots and Wings. I was in my late 40’s at college, finishing my masters when I first started selling my works, before that, I mostly gave it away.” School had truly given Sue her wings and at the same time provided her the opportunity to recognize how her past experiences became her roots. It was up to her now to forge the two together. It was only after Sue moved to Seattle (1998) that she decided without a doubt to seriously take on the challenge of her art career. Sue was met with a modicum of success in the Northwest with a kind of starting over; a redefining. Sue became a member of the Northwest Watercolor Society (2004), Artists Connect (2004), Seattle Co-Arts (2006), and the Women Painters of Washington (2006) where she served as Vice President and Program Chairman of the WPW during 07-08, and President (2010-2011). She is also a member of the National Association of Women Artists, New York City.

“Tama Nathan gave me a lithograph when I finished my Masters in 1990 titled, To Sue, Who Now Has Roots and Wings. I was in my late 40’s at college, finishing my masters when I first started selling my works, before that, I mostly gave it away.” School had truly given Sue her wings and at the same time provided her the opportunity to recognize how her past experiences became her roots. It was up to her now to forge the two together. It was only after Sue moved to Seattle (1998) that she decided without a doubt to seriously take on the challenge of her art career. Sue was met with a modicum of success in the Northwest with a kind of starting over; a redefining. Sue became a member of the Northwest Watercolor Society (2004), Artists Connect (2004), Seattle Co-Arts (2006), and the Women Painters of Washington (2006) where she served as Vice President and Program Chairman of the WPW during 07-08, and President (2010-2011). She is also a member of the National Association of Women Artists, New York City.

“It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.”

Pablo Picasso

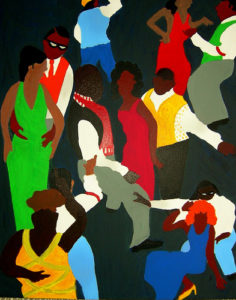

There is a dichotomy in Sue’s work because the kind of work that she really enjoys most is naive or primitive. Her work would be classified as such but she had to learn the style as a technique. She would dread for a viewer to think that her work is immature; but, because of the shear nature of the term, Sue can never truly be a part of that discipline. She purposely aligns her art with the Naive and Primitive Art style but approaches it from a different angle. She has been fortunate to have had the opportunity to have studied the rules, the absolutes, and the basic concepts. In one way you could say she is painting in the primitive method but in another way you could say that she could never in reality belong to that school. Sue has her own sense of composition; a sense of style, but Naive and Primitive by definition will never be completely natural for the academically educated. Sue has a natural love for the primitive or naive but for her, it is not a natural style; it is more learned than innate.

I usually work in a quiet place. I use photographs sometimes, but I don’t copy because I think it is wrong to copy, but I will have an idea and put two or three different images together to come up with a composition. I would never want to hear that my work “looks like it came from a photograph” because then I have missed the mark. I don’t want a photographic likeness…your insight is more important that your sight.” Sue achieves her paintings by sticking to only three round brushes and because she likes vivid, flat color she sometimes works on as many as three canvases at one time. “I will have to put two to three layers on to get the flat look that I want. I like to work from the background forward, especially in a series, I want all the backgrounds to be the same and I will apply the same color on all of them. So sometimes it takes me two days to get the background done. Sometimes I use a light wash of colors so I can see how the adjoining colors are going to react to each other. I want to repeat and I want to balance my colors. But I save the main subject focal point and details for the last.”

I usually work in a quiet place. I use photographs sometimes, but I don’t copy because I think it is wrong to copy, but I will have an idea and put two or three different images together to come up with a composition. I would never want to hear that my work “looks like it came from a photograph” because then I have missed the mark. I don’t want a photographic likeness…your insight is more important that your sight.” Sue achieves her paintings by sticking to only three round brushes and because she likes vivid, flat color she sometimes works on as many as three canvases at one time. “I will have to put two to three layers on to get the flat look that I want. I like to work from the background forward, especially in a series, I want all the backgrounds to be the same and I will apply the same color on all of them. So sometimes it takes me two days to get the background done. Sometimes I use a light wash of colors so I can see how the adjoining colors are going to react to each other. I want to repeat and I want to balance my colors. But I save the main subject focal point and details for the last.”

Sue purposefully paints subjects that come across as happy. Although she claims no allegiance to abstract art at this time, “I may be going in that direction because there is some abstraction in my current art. I like patterning and the use of flat color and I like that it is still evolving and right now I am having fun doing what I am doing. I enjoy it, it is not labor.” When her focus was on watercolors, Sue found that she tended to overwork her pieces as she kept trying to achieve vivid and bright colors. With acrylics, the medium itself allows her to attain true color richness. Her formal training instilled two things – composition and color. “If the composition is not good then it is not a good painting. If you are not smart in your use of color then your painting is tepid. My Daddy always taught me when playing Poker that you always need a kicker at the end which is something that I put in my painting, you need a spot of yellow or a spot of red, you need a focal point to draw the viewer back in to the painting.”

“The best thing a viewer can say about my work is that it makes me smile because I want to accomplish a sense of joy while maybe poking fun at some traditions and I am hopeful that it shows in my work. I think that there is beauty in the mundane and the things that we take for granted. I enjoy doing this work. Right now I have seven canvases I’m currently working on and I can’t wait to get back to them. If I had a legacy of my art it would be for people to think that there is fun, color, and humor in everyday life. That is how I would like for it to be recognized. It is every artist’s goal to be remembered period, that would be nice. Someday I hope to be remembered as maybe Grandma Roses, like Grandma Moses (1860-1961). I would want to be remembered for my color and my vividness. I believe that there has to be something unique about your art for you to be recognized. Have I gotten there yet? I think right now I am getting there, but I don’t think I have been there before.”